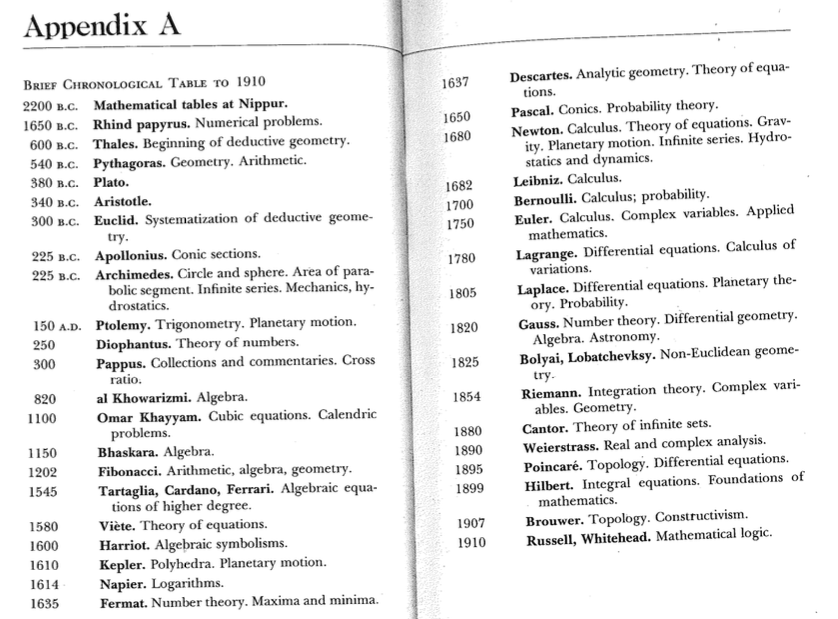

I was assigned a chapter to read from The Mathematical Experience in a math education course in 2018 while getting my masters. This page was included in the reading. Take a moment to read through it. What do you notice? What do you wonder?

I noticed in my first pass at this page, I tried to see whose names I could recognize from this list. Like looking at the cast list for a movie you’re about to watch, or skimming the program for a high school graduation: Oooh, I’ve heard of Napier logs, Fibonacci numbers, and Riemann sums!

Upon closer inspection many years later, the scan is different: Which of these names do not belong to a white European man? What was the criteria necessary to make it onto this timeline? Was it notable discoveries in mathematics? How notable is notable?

No, it was white discoveries in mathematics, known for their white “discoverers.” Who gets to decide that this chronology is “the” mathematical experience?

This fall during my first semester of my Ph.D. program I was assigned The Racial Contract by Charles Mills (1997). The Racial Contract is Mills’ counter to the European “social contract,” whereby an a government protects a group of people in exchange for a few rights. Mills’ argument is that the group of people protected under the social contract is white, and “nonwhites” are not counted as people, and thus do not receive the benefits and protections of this contract. Therefore, it is not a social contract that governs all spaces, but a racial one.

Mills gave me a framework to unpack my critiques about the image above from The Mathematical Experience and language to more closely examine various structures of whiteness in the mathematics classroom that have largely been unquestioned during my mathematics education. This blog post is the beginning of that unraveling. My hope is through my reflection of my mathematical experiences, you might engage in your own reflection, and perhaps even reflect with your students.

Positionality

I am a first (1.5?)-generation Chinese American, English-speaking, able-bodied, middle-class, queer millennial who was socialized as a woman throughout my youth. I attended public schools in Florida for the entirety of my K-12 education, and I participated in mathematics competitions from 4th grade through 12th grade. I eventually served as co-president of my high school Math Club and studied AP Calculus BC my senior year of high school. I decided not to major in economics during the fall of my first year of college at Harvard after faltering in multivariable calculus. I decided that I was “no longer a math person.” I eventually found my way into mathematics education and taught public high school mathematics for eight years in the Greater Boston Area before starting a Ph.D. program in mathematics education, where I am right now.

What Counts as Mathematics

Mills’ first writes, “standard textbooks and courses have for the most part been written and designed by whites, who take their racial privilege so much for granted that they do not even see it as political, as a form of domination” (p. 1).

Mathematics textbooks are no exception. The following are the mathematics textbooks that I had throughout my youth:

- Addison Wesley (various, grades 4-7)

- McGraw Hill (various, grades 4-7)

- Serra’s Discovering Geometry (the rotating hands one)

- Larson’s Single-Variable Calculus (the stringed-instrument f-hole one)

- Stewart’s Single-Variable Calculus (the 3D mobius strip / umbilic torus one)

- Stewart’s Multivariable Calculus (the wavy architecture one)

- Bretscher’s Linear Algebra (the ambiguous lines and circles one)

White men, and thus white ideas dominated the voice of the mathematics textbooks that instructors used, and no one ever named for me that this is a form of domination. It is the very nature of unnamed, unchecked whiteness that permeates the source text of the mathematics curriculum I was given, the foundations of the mathematical knowledge I have today, and that prioritization, that “white epistemic authority” (p. 18) has informed my mathematical upbringing.

Who Gets To Do [Whose] Mathematics

I remember coming home from school and asking my mom for “white people food.” Rather than homemade dumplings with “stinky” garlic chives, I wanted the “scent-neutral” ham and cheese sandwiches in a plastic zip-lock bag with a Capri Sun and a bag of Lays chips in a brown paper bag with a note—the food of my white classmates at the lunch table. The lunch that was leftovers packed in a Chinese takeout soup container was inferior at the lunch table, where social status was dictated by lunch acceptability.

Part of what it means to be constructed as ” white,” […] part of what it requires to achieve Whiteness, successfully to become a white person (one imagines a ceremony with certificates attending the successful rite of passage: “Congratulations, you’re now an official white person! “), is a cognitive model that precludes self-transparency and genuine understanding of social realities.

(Mills, 1997, p. 18)

Here Mills speaks of an epistemology of ignorance, whereby whites are “in general unable to understand the world that they themselves made” (p. 18).

I invite myself (and you) to think of the mathematics that I learned as “white people math.” This means that when we learned the multiplication table in the third grade and played “Around the World,” a speedy verbalization competition where you had to say the correct answer as quickly as you can or risk being unseated by your challenger, I was doing my best not to blurt out my answer in Mandarin, for I had learned at home how to multiply, quickly, using rhymes in that language. “White people math” meant that the way I had learned to count on my fingers at home was weird or wrong when I got to school because everyone else held up “3” with their thumbs touching their pinkies, and I had learned it with my thumb touching my index finger. This means that my parents, who both had received high school education equivalents in China, could not help me with my mathematics homework because the names of the theorems were different.

“White people math” also means that my mother, who engineered magic tricks as part of her trade to get us to be able to stay in the United States was not seen as a mathematician, despite the precision in which she calculated the timings of her magic and the ingenuity and creativity that went into her trick and prop designs. In fact, my father led the charge at home of the messaging that “your mom is bad at math.”

Yet, no one ever stopped me to a) invite my home-ways of doing mathematics into the conversation at school, b) recognize that we are learning “white people math” at school, or c) share that there even is such thing as non-white people math.

How We Do Mathematics

In geometry class, I was first introduced to the concept of a “proof.” We were told that there were four main types of logical reasoning that we could employ in order to create a proof—modus ponens, modus tollens, law of the contrapositive, law of syllogism. Using these, we learned to “prove” things in mathematics, which is what we were told was the “highest form of certainty” that could be achieved.

Later, I took a proof writing class during my masters, and the kinds of language we were asked to use felt unnatural with the English:

- For every ___ in ___ such that ___

- Assume that ___

- Let ___

- Without loss of generality, ___

For starters, no one speaks like this. Yet in this proof writing class, we were told that these were “formal” ways of writing. That this is what is correct and what is accepted in the field. (“Congratulations! You’re now an official [white] mathematician!”) Tanswell and Rittberg (2020) explicitly list this kind of teaching proofs as an example of epistemic injustice for its exact linguistic complexity for no apparent reason rather than an obsession with parsimony in the field.

Who (Or What) Mathematics Is For

Much of my teaching of high school mathematics was spent with students who often asked the question, “Why do we need to know this”? Here is a list of possible answers:

- Because it’s going to be on an upcoming test

- Because I said so

- Because someone else said so

- Because it will help you get a job in a STEM field, which will lead you to make lots of money

- Because it’s fun

- Because it’s beautiful

- Because it’s useful

- Because it’s relevant to this one aspect of your life, but only tangentially

The reality is that the question of utility, “why” or “for whom/what” never came up in the mathematical spaces I inhabited prior to my starting to teach. That is the unchecked racial contract at play.

What characterizes this period (which is, of course, the present) is tension between continuing de facto white privilege and this formal extension of rights. The Racial Contract continues to manifest itself, of course, in unofficial local agreements of various kinds (restrictive covenants, employment discrimination contracts, political decisions about resource allocation, etc.).

(Mills, 1997, p. 73)

As a mathematical student, I had subjected myself to the agreement, though restrictive, of that mathematics is and would offer me that I never questioned why is it that we do the mathematics. I did not feel the need to, and no one else ever questioned it. This is more of Mills’ epistemology of ignorance at play. The degree to which truth in mathematics is proven via a strangely worded series of sentences is accepted and unquestioned to one group of people (mostly middle class white, East Asian and South Asian at the high school I attended) and is different and constantly questioned by another group of people (mostly working class Latine and Black students at the high schools I taught). Mathematics is useful, beautiful, fun, and relevant to whites (and white-adjacent people), but its use, beauty, funness, and relevance are not part of the experience of Latine and Black students is the racial contract at play in mathematics and mathematics education.

Continuation

Rather than concluding here, I encourage you to think about your mathematical experience and find moments of oddity and injustice that can only be explained by the existence of a racial contract. I hope that through this reflection, you might also rekindle a few mathematical ways of knowing that were previously de-emphasized to re-center the white narrative. I invite you to post any examples you reflect on in the comments below. My hope is that collectively, we can realize that each one of us gives the story of a mathematical experience, which collectively counter the idea of “the” mathematical experience.

References

Hersh, R., & Marchisotto, E. (1981). The Mathematical Experience. Frome, London: Butler & Tanner.

Mills, C. W., Mills, C. W., & Cornell University Press. (1997). The Racial Contract. Cornell University Press. https://books.google.com/books?id=LPbBdyxGNhQC

Tanswell, F. S., & Rittberg, C. J. (2020). Epistemic injustice in mathematics education. ZDM, 52(6), 1199–1210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-020-01174-6